This Lady Loves the Tramp by Cristina Ann Correa

Posted on May 30, 2018

By Cristina Ann Correa

Do you DIY?

In a day and age where Pinterest boards multiply more quickly than rabbits, it seems like just about everyone has tried their hand at handmade.

Innovative, quirky, and in best-case scenarios, fully functional, the world of do-it-yourself has become the source of bragging rights, hit TV shows, and memorable memes.

Long before Chip and Jo-Jo became the reigning royalty of repurposing, however, a group of industrious artisans redefined resourcefulness. If you thought you'd seen amazing, buckle up and get ready for a ride.

Nestled warmly within the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA), an eclectic array of intricately carved tramp art greets visitors like an old friend. No Idle Hands, which opened to the public in March of 2017, features over 150 tramp art objects collected from around the world. The first feature of its kind since 1975, this carefully curated exhibition helps educate viewers about the highly skilled, ingenious works created from discarded cigar boxes and fruit crates.

Contrary to popular belief, tramp art was neither created by train-hopping hobos nor cute dogs in Disney movies. Rather, this notched and layered style of woodworking from the late 19th and early 20th centuries was thoughtfully created by artisans, farmers, factory workers and self-taught wood carvers. These family men knew that necessity was the mother of invention and recycled wood to create ornate, decorative and useful household objects.

Teetering oh so carefully between folk and fine art, the works in No Idle Hands prove that brilliant creativity and craftsmanship can exist outside the boundaries of art school and gallery space.

As a painter and lover of lively color, I was immediately drawn to the gorgeous works of contemporary artist Freeland Tanner. This California native, whose primary career is landscape designer, gracefully wrangles inspiration from American folk art with modern technology to create three-dimensional tramp art that engages harmoniously with its space.

Tanner's most recent works in the exhibition are a trio of constructions inspired by New Mexican tin art.

Freeland TannerLeft to Right: Valencia, El Corazon Secreto & Hermosas Flores, 2016Wood, beads, brass hardwareCourtesy of the artist

Utilizing American folk iconography and the characteristic V-shaped notching, Tanner's playful and vibrant artworks beg closer inspection. Subtle nuances illuminate the melding of American domesticity with a masculine refinement. What I find to be most visually striking is the way the trio conjures up memories of the whimsical repujado, or embossed surfaces, that line the open air markets of deep south Texas. Tanner's meticulous repetition of texture and shape elevate the works to fine art while maintaining tramp art's humble origin.

Tucked more deeply into No Idle Hands, is another such configuration.

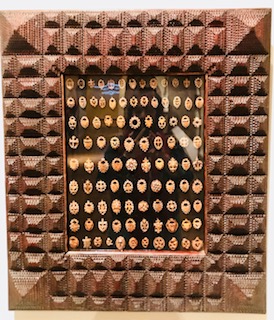

Museum of International Folk Art, IFAF Collection (FA.2015.55.1)

At first glance, Henry J. Bolieau’s tramp art frame loosely resembles a shadow box proudly displaying a collection of jewelry. A closer look reveals, however, a complex and complicated compilation of carved peach pits inlaid with rhinestones.

A firm believer of figuring out how to make limited supplies and budgets ‘work,’ my mind buzzes with Bolieau’s revolutionary use of the peach pits. Talk about transformation!

The best kind of art needs little explanation, and Bolieau’s extraordinary redesign and repurposing of the richly-colored pits makes me wish I could reach into the frame and claim one to wear as a brooch or necklace. Juxtaposed against the lustrous, cherry finish of the reclaimed wood, the artwork is as cleanly composed as a modern-day graphic design.

While there are many other magnificent visual points of interest in No Idle Hands worth sharing, its solitary sailor’s valentine resonates most significantly within me.

Like tramp art, sailor’s valentines are an ingenious manifestation of the Victorian Era. While the mosaic-like patterns of exotic shells were said to have been a product of a sailor’s lengthy travel at sea, contemporary historians have attributed the compositions to souvenir shops in the West Indies.

Rather than being housed in a compass box, this anonymous sailor’s valentine is securely mounted within a tramp art frame accented by progressively lighter wood stains. Splashes of green seaweed and glimpses of red patterned paper balance the symmetrical, and in places, floral, composition of shells.

My grandfather, who traveled through the Caribbean, Central and South America for his horticultural work, brought a large sailor’s valentine back to Texas for my grandmother in the 1970s. The composition, which resembles flowers contained in a vase, was one of my grandmother’s most prized possessions and hung on the wall across from their front door for nearly 40 years.

Until viewing No Idle HandsI had simply assumed that the shell collage adorning the mint green paper was another antique object in my grandmother’s assortment. Realizing the work was part of an established folk industry both excited and endeared me to it even more. Despite being geographically isolated from the rest of the country in deep south Texas, I suddenly felt as though our footprint could be connected, even if in the tiniest of ways.

The power of the tramp art contained within No Idle Hands, and more importantly, the folk art collection of the MOIFA, is this capacity to connect the viewer with the global community. The art of the craftsman is a bond between peoples of the world. While some argue that folk and fine art exist in two separate realms, the artist in me challenges this convention with each successive visit to the MOIFA. Yes, in its original context, tramp art was largely intended for a utilitarian and conventional purpose, but by today’s standards of craftsmanship, its constructions are as superb and imaginative as works I’d expect to see in a contemporary exhibition.

So if you do DIY, -or even if you don’t, -take the trip to Museum Hill and let yourself get lost in No Idle Hands. It, along with the MOIFA’s incredible collection of folk art, will change your perception of what could be.

Latest Posts

-

COVID-19 Embroideries

- Nov 10, 2022 -

Guru Mahatmya

- Jul 20, 2021 -

The COVID-19 Pandemic from an Indigenous Perspective

- Feb 17, 2021 -

Docent's Choice

- Jul 23, 2020 -

Folk Art Piece of the Week - Docent's Choice

- Jul 02, 2020